A Sense Of Déjà Vu

Exploring the parallels between the train derailment crisis in East Palestine, Ohio and the film White Noise

“Talk about art imitating life. This is such a scary situation. And you can just about drive yourself crazy thinking about how uncanny the similarities are between what’s happening now and in that movie.”

—Ben Ratner, East Palestine resident and extra in the film White Noise

I imagine everyone has heard about the situation in East Palestine, Ohio, as the mainstream media has recently decided to cover the story. Similar to pretty much all big events that take place these days, there’s a maelstrom of suspicious information that leads to confusion. I have taken in all that I can from many different angles, and am aware of many bizarre threads in the story. I also have a reporter friend who is boots-on-the-ground in East Palestine telling me what he is witnessing and hearing firsthand.

I saw really excellent coverage on the event from the perspective of it being a deadly, toxic crisis, and I’ve also seen content claiming the whole thing is a false flag, no one wearing PPE, no proof via samples of toxicity. I know about the My-ID program, the claims of the CDC changing something a few weeks ago, the odd elements of the train crash itself, its speed, footage of it being on fire long before its arrival in East Palestine, the controlled explosion, and the private police brought in from Norfolk Southern. I’m going to leave all that to the competent reporters I personally know looking into all this via the expertise they have in their specific fields—and the fact that they are there on the ground taking in the best evidence, first-hand experience.

Over the last couple of weeks, a number of people reached out to me asking if I thought the story was real or a psyop—whatever that may mean in this case. I took a backseat and simply bore witness to the media’s (both MSM and alternative) response to the situation for a time. (The way information circulates regarding a particular event can tell you a lot about the nature of that event.) I didn’t immediately know how to approach the question, but eventually I leaned back on my main interest and skill, which is deciphering possible intent in real-life events through propaganda.

I found myself particularly interested in what could possibly be discovered through an analysis of one very bizarre element of the story: the fact that a film, White Noise, was shot in the region last year, involving the participation of locals of East Palestine as extras in the movie. The film literally told the story of a train crash and subsequent toxic explosion that required the area to evacuate with lingering fears of exposure and the highlighting of possible long-term health defects, most notably death.

To be clear, my understanding is that the film White Noise was shot in multiple locations across Ohio, some very close to East Palestine, but it wouldn’t be accurate to say the film was shot in East Palestine. However, it would be accurate to say that people from that whole region of Ohio expressed a great deal of excitement from their sleepy, blue-collar towns, feeling honored that their working-class strip of Ohio was selected for such a high-caliber production. There was a buzz about the film and many people from the region signed on to be extras, including some from East Palestine.

The eerie “prediction” that the film makes of the shortly-thereafter-to-manifest, real-life disaster has led to quite a bit of media attention. CNN, New York Post and others ran pieces with headlines such as After a train derailment, Ohio residents are living the plot of a movie they helped make or Deadly Ohio train derailment eerily “predicted” on Netflix: “Scary”.

Terms such as “parallel,” “prediction,” and “odd coincidence” have been used. I found myself wondering what the filmmakers and actors were thinking now that this tragic and catastrophic “fictional scenario” has become reality for the people actually living through this nightmare.

I decided to do a deeper dive into the film.

I watched the movie attempting to hold two separate questions simultaneously: Was this simply a morbid coincidence? Or is the movie a form of communication reflecting something premeditated? I do not recommend watching the movie. It is stupid, irreverently morbid, and terribly difficult to watch in light of people’s real grief and pain at the moment. Nonetheless, you shouldn’t take my word for anything. Investigate things on your own which may include watching the film. If you do, I encourage you to at least attempt to hold the previously mentioned two questions in some sort of intentional balance. Do the best you can.

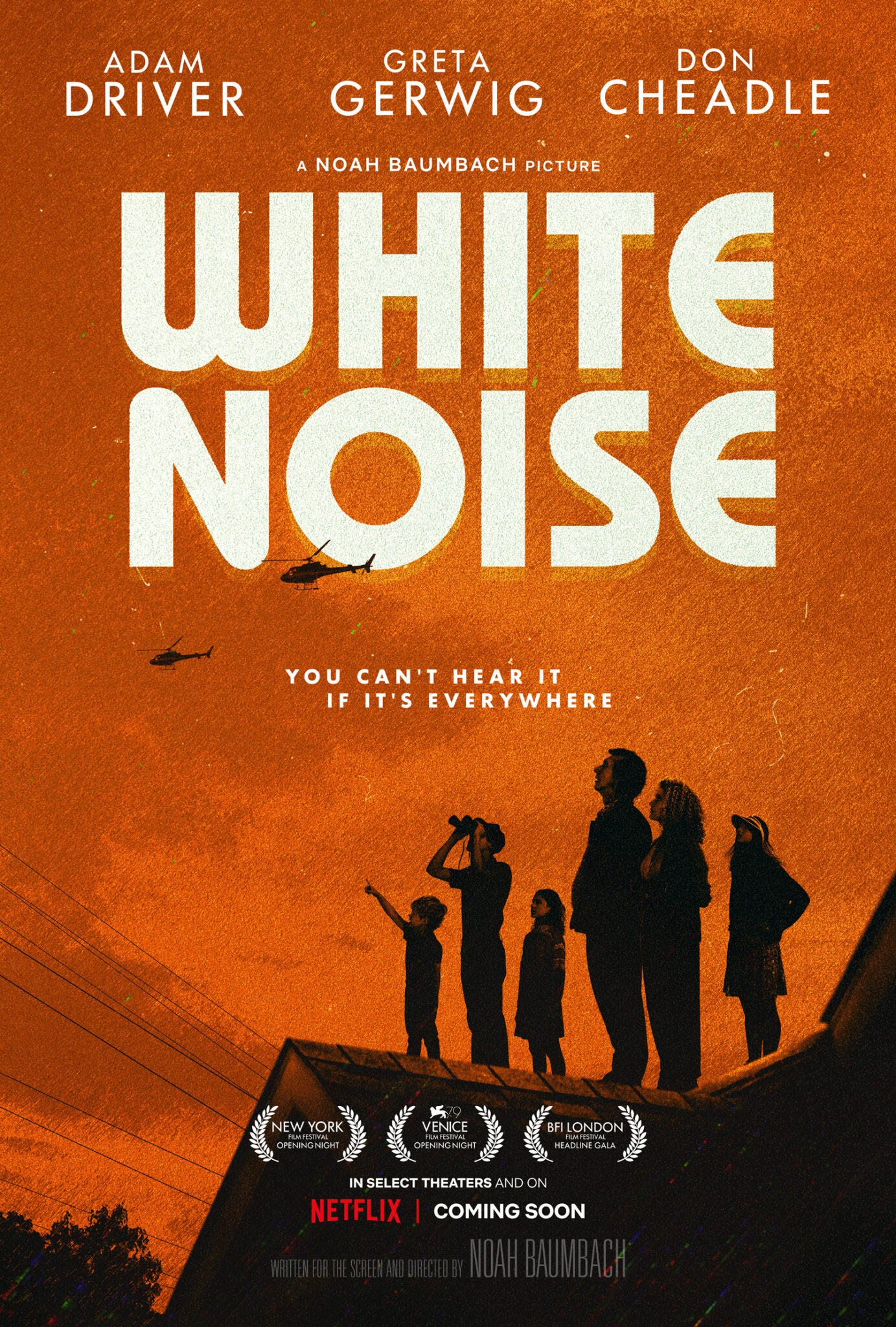

The film is adapted from the book by the same title, written in 1985 by Don DeLillo. It is considered a postmodern dark comedy. The author is a professor of postmodernism; therefore it’s no surprise that nihilism abounds.

Released in the U.S. just three months ago in November 2022, here’s the movie’s basic plot:

White Noise follows a year in the life of Jack Gladney, a professor at the College-on-the-Hill who has made his name by pioneering the field of Hitler Studies. He and his wife Babette have four children between them.

The film has three sections. The first called “Waves and Radiation” introduces the characters and moves back and forth between Jack’s life teaching at College and scenes at home with his family.

The second section, “The Airborne Toxic Event,” describes a train derailment near Jack’s town that releases a toxic cloud filled with the fictional Nyodene Derivative. The town is evacuated and Jack discovers he has been exposed to the chemical long enough that he will die from it.

The third and final section of the movie, “Dylarama,” reveals Babette has offered herself as a human test subject for a fictional drug not yet on the market called Dylar. It is supposed to cure people of their fear of death, or terror of death. She tells Jack that she had to sleep with the main drug developer, Mr. Gray, in order to gain access to the drug. Jack shares in the fear of death, especially now that he’s been told he will die due to toxic exposure. A friend of Jack’s successfully convinces Jack that he can cure himself of his own fear of death by killing someone. Jack tracks down and shoots Mr. Gray.

Part One: Waves and Radiation

Obsession with car crashes, plane crashes, catastrophes—televised, fictional, or real

The film begins with a montage of scenes from old movies showing car crashes, with Jack’s professor-friend Murray sharing his enthusiasm for fictional accidents in film. This enthusiasm we later learn is a central part of his character as he is obsessed with both Hollywood car crashes and Elvis.

Murray describes the iconic car crash in a film as “something elemental, a high-spirited moment.” He goes on: “What about all the blood and broken glass you may ask? . . . innocent, and fun!”

The theme of televised crashes and catastrophes continues throughout the film. Just a few scenes later we see Jack with his family glued to the television to watch footage of a real plane crash that we are told has just occurred somewhere else in the country.

In another scene that stands out on this theme we see the professors chatting in the College cafeteria. The topic of televised catastrophes comes up. This is the conversation between three or four of them:

“It’s natural, it’s normal that decent, well-meaning people would find themselves intrigued by catastrophe when they see it on the television.”

“We need the occasional catastrophe to break up the incessant bombardment of information.”

“The flow is constant: words, pictures, numbers, facts, graphics, statistics. . .”

“You’re saying it’s more or less universal to be fascinated by TV disasters.”

Then in a notably nihilistic shift, they discuss defecating in lidless toilets and the fetish of urinating in sinks.

Hitler, Elvis, controlling crowds, a train crash, and an explosion

In one of the more fascinating scenes in the film, Jack visits Murray’s class to talk about Hitler while Murray simultaneously talks about Elvis. They are both describing their subject’s relationship with their mother. The setting for the scene is a bizarre college classroom. Though there are college students present, it looks more like a small child’s playroom with brightly colored rainbows.

In a previous scene, while referencing Hitler, Jack had made the comment that “when people are afraid they are attracted to mythic figures.”

The scene escalates as Jack describes the crowds that formed around Hitler for his speeches. Here the scene is injected with short black-and-white clips of Hitler and the crowds that formed in his presence. It then cuts to a shot of an oncoming train and a tanker truck filled with flammable material heading toward the train track. Then, the scene moves back and forth between footage of Hitler’s crowd and footage of a crowd of screaming girls at an Elvis concert, while Jack describes how we all want to be part of a crowd.

“What is the difference between these two crowds?” he asks. Then he stoops down low and in a guttural, raspy voice utters a long, drawn out “death.”

Not that those people had died yet, he goes on, but rather that they were marked to die. At that moment he points his finger directly at the forehead of a young student as if targeting him.

Cut to footage of the train crash, a close-up shot of liquid leaking from the train cars ominously suggestive of blood, the massive explosion, and then lastly, a brief black-and-white clip of someone seig heiling. A culminating . . . a finale of sorts.

Now, it should be noted that although the technology clearly exists to create a CGI simulation of the train crash and explosion, the director, Noah Baumbach, chose to stage an actual train crash and explosion. This can easily be explained as an aesthetic choice given the shortcomings of CGI. Nonetheless, it is certainly worth noting that a staged train crash and explosion happened in an area that would go on to have exactly the same scene play out again in real life.

Baumbach describes the movie, shot on film, as a "period piece." The costumes and cars very much belong to the 1980s, and it features a complex car chase (with a flying family station wagon) and a fully staged train crash.

“It was a rig but it was pulled into the train and timed out and everything. We did a lot of the detail work separately of the canisters hitting each other," Baumbach said. "It does have a lot of visual effects in it as well, but they're designed to work with the same aesthetic."

Part Two: “Toxic Airborne Event”

Fear of tiny unseen deadly particles, shortness of breath, and a sense of déjà vu

Jack and his family are home, navigating whether or not to be concerned about the distant plume of smoke rising from the train crash. Jack has recently had episodes of waking up, hallucinating, and gasping for air. The family sees emergency vehicles rushing past the house, and the son feeds them information from the radio about the unfolding situation.

The son has learned what the substance is and tells his parents what symptoms were discovered when it was tested on rats. (The theme of comparing rats to humans comes up multiple times in the film.) The symptoms, he says, are nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, and sweaty palms. He then goes on to share newly updated information he has just received that the symptoms are heart palpitations and a sense of déjà vu.

Yes, you read that right. A sense of DÉJÀ VU.

Definition of déjà vu: A feeling of having already experienced the present situation.

It’s hard to imagine that the people of East Palestine, Ohio, aren’t currently experiencing a sense of déjà vu.

A few scenes later, after another discussion between the children about rats, the family has been evacuated to a camp lodge. There, Jack runs into his professor-friend Murray who asks him, “Any episodes of déjà vu in your group?” and then repeats the question as if to simulate a moment of déjà vu. He goes on, “Why do we think these things happen before? Simple. They did happen before, in our minds as visions of the future.”

Still at the camp lodge, Jack realizes he has been exposed to the toxic chemical and gets in line for some sort of toxic disaster-management assessment. The young man doing the assessment is sitting behind a desk typing away at a computer, and goes on to tell Jack that the situation doesn’t look good for him. Jack notices the young man is wearing an armband with the word “SIMULAC” on it and asks him what it means. The young man says it stands for “simulated evacuation,” and that he is part of a group that simulates evacuations during simulated disasters. Jack asks him if the disaster they are experiencing is real, to which the young man replies, yes, it is real. We just thought we’d take advantage of the real disaster to practice our simulations.

The theme of real versus simulated is woven throughout the film. What is real on TV? What is real that comes out of Hollywood? Are the people in the film in a simulation or not?

Even the author, Don Delillo, described part of his inspiration for the book back in 1985 in the following way:

“I kept turning on the TV news and seeing toxic spills and it occurred to me that people regard these events not as events in the real world, but as television—pure television," DeLillo himself told NPR at the time that White Noise was published.

Another example of conflating reality with televised fiction is a scene further into the movie where Jack and his family have been moved to a new evacuation location. There, a man holds an unplugged TV atop his head and begins ranting loudly about being quarantined and imprisoned. He says, “Do they think this is just television? Don’t they know this is real? Isn’t fear news?”

Violence as a liberator

Later, Jack confides to his friend Murray that he has been told he will die due to toxic exposure. Murray gives him a gun, all the while babbling about killers and those that are killed. Though he says he realizes Jack isn’t a killer, Murray says who knows?, perhaps it would free Jack from his existential burden, explaining that “maybe violence is a form of rebirth.”

Part Three: Dylarama

Terror of death, psychobiology, and the consumption of untested pharmaceutical products

The final part of the film focuses on fear of death. It’s a strong red thread throughout the whole film, beginning with an early scene in which Jack and Babette discuss their fear of death in bed. As the film progresses we learn that Babette has been taking some kind of pharmaceutical drug and has been keeping it a secret. Her daughter is very concerned about her. She discovers the pill bottle and researches the drug inside, Dylar, but cannot find it listed in medical journals or at the pharmacy.

As Babette’s mental-emotional health deteriorates, Jack confronts her. She tells him that she has been taking the drug due to a condition she was unable to manage and that the drug is not available on the market. She shares that she offered herself as a super-secret test subject in the drug trial, described as a psychobiology product, in order to get the medication. But the trial collapses leaving her no other option than to sleep with the project manager, Mr. Gray, who then supplies her the medication in exchange for sex. Jack calls her a “human test animal.”

Definition of psychobiology: The branch of psychology that studies the biological foundations of behavior, emotions, and mental processes.

After some upset, Jack asks Babette what the condition is and she replies, “fear of death.” (In the book, Dylar is described as a medication to manage terror of death.)

Babette is sobbing. She says she knows Jack is afraid of death too, but that she is really, really afraid of death. She tells him that she loves him very much, but that her fear of death is greater than her love for him. She is crippled, rendered incapacitated by this fear and buries herself in the sheets.

It is at this point in the film that the parallels between the story and reality are hard to ignore. Is not the fear of death our greatest weakness? To what lengths would you go to access an experimental, untested pharmaceutical product that is purported to save your life and put your mind at ease?

Jack ultimately shoots, though doesn’t kill, Mr. Gray, who he has managed to track down and found in a zombie-like state due to his addiction to Dylar. Jack and Babette decide to save Mr. Gray and take him to a hospital run by atheist nuns. The whole film concludes with an odd dance scene.

The film rather magically dances between themes and propaganda tactics weaving a dreadfully dystopian death-cult-centric world. It vacillates back and forth between enormously tragic content and irreverent nonsense. One might even get the sense the story is told by someone laughing at the plight of human beings. There is a constant touching on the themes of media, propaganda, real, simulated, televised. Catastrophes as entertainment is difficult to digest given the déjà vu the people of East Palestine must be experiencing right now.

The film suggests a parallel between Hitler and Elvis by the effect they had on their audiences, inviting us to ponder the difference between the power of Hitler and the power of entertainment. Specifically, the film invites us to ponder the American entertainment industry based on the beginning of the movie in which Murray tells his class that scenes with car crashes in films made outside the United States pale in comparison to those put out by Hollywood where the finest quality of simulated vehicular crash scenes are produced.

I have been wondering what it must be like to have participated in the making of this film, only for those involved to then go through the experience in real life. What do these locals think about the movie?

According to Ben Ratner, who signed his whole family up to join the production as extras, trying to go back to watch the movie is now gut wrenching. In an interview with People, Ratner said:

"I went and tried to watch the film a few days ago and couldn't," he admits. "It wasn't something I wanted to be entertained by because for us, it's a real-life situation. All of a sudden, it hit too close to home.”

I can only imagine to locals like Ratner that it certainly does feel like they’ve been the target of a bona-fide psychological operation. His comments make clear he is in a state of mind the symptoms of which result from the psychological confusion the situation has rendered in people. He has to live now with the odd reality of having one foot in fiction and one in real life, just like the story line of the film. White Noise’s two major themes—a) fictitious, simulated catastrophes paralleled with real-life catastrophes and b) an unseen deadly toxin’s effect of déjà vu—is too painfully marked not to notice.

This film is more than a remarkably disturbing parallel between fiction and reality. It is an opportunity for the hard-working, good people of America to respond with a cri de coeur:

We don’t want to participate in a game of fiction versus reality.

We don’t want your nihilism, your postmodern atheism.

We don’t want our plight cynically laughed at, made fun of,

treated like content for promotional purposes.

We don’t want our minds bent by a love of Hollywood-staged,

extravagant, costly vehicle crashes of any kind.

We don’t want the “I can’t breathe” agenda.

We don’t want the Hitler-infused, race-baiting agenda.

We don’t want the “be afraid of the tiny unseen particles

that are all around you and will kill you” agenda.

We don’t want untested pharmaceutical products

that come out of the field of mental/behavioral studies.

We don’t want any untested pharmaceutical products, period.

We don’t want to be conflated with test animals and rats.

We don’t want our fear of death taken advantage of

to get us to do immoral things.

We don’t want your toxic shit in our communities.

WE DON’T WANT YOUR DYLAR!

Great review, Kristin Elizabeth. More and more, it seems the world is asking us to develop our intuition, our sense of truth, and living in the unknowing in the mean time.

Very helpful, thanks!