The Minotaur, the Mad Farmer, and the Wise Child

For context, I encourage you to read my piece “What is Cognitive Warfare?”

One of the most damning things I see daily is people sharing propaganda that is intended to go viral for any number of nefarious reasons, as if it were created by an ally who wishes the best for humanity and wants everyone to “wake up.” There is, on the one hand, the legacy media narrative, a parallel for abusive censorship. It dominates from one side as the power establishment, and sets the stage for the dissenting side which would naturally be the free flow of information and uncensored truth.

In reality, within the freedom movement’s information-sharing spaces, there is a constant, daily injection of mind-bending nonsense that over time has shaped people’s paradigms and consciousness — and not always for the better. What results from the establishment dissident dialectic is unearned trust in anyone presenting themselves as a dissident. This dilemma seems to be unnoticed by those who consume such media claptrap.

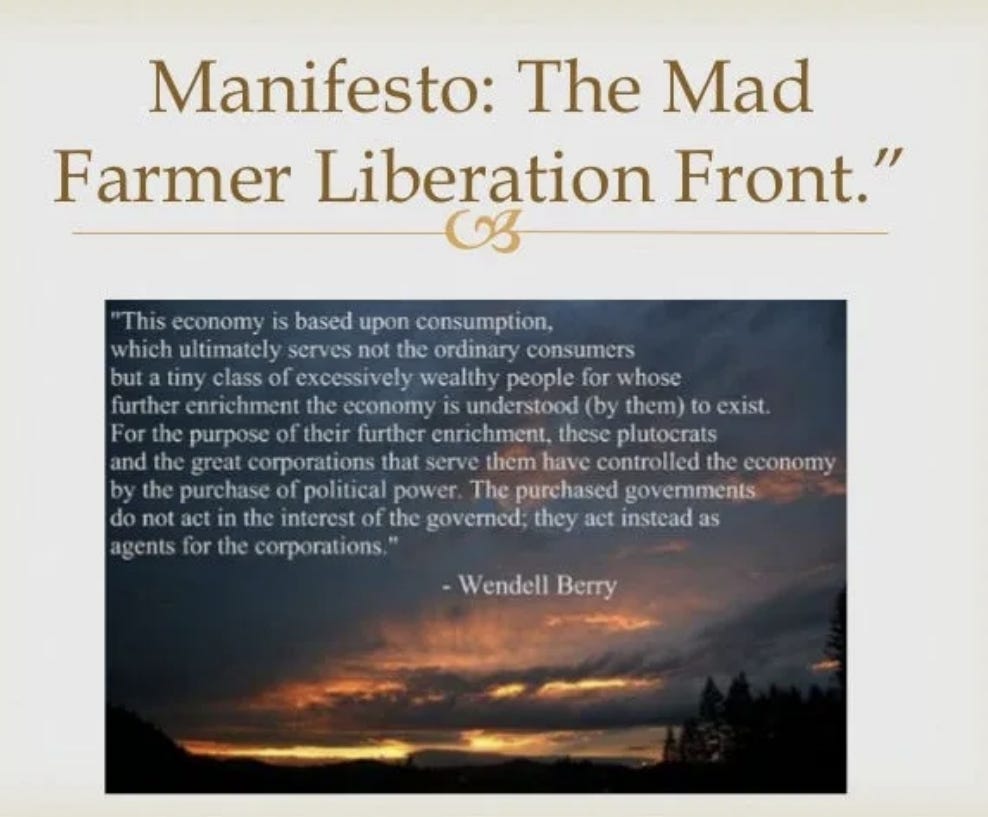

This screenshot is an extreme example of propaganda tailored to a specific audience. Within the population that moved away from mainstream media and toward uncensored, “secure,” social-media spaces, a version of this kind of content is aimed at most sub-demographic groups therein. Whether you found yourself in these alternative info-sharing spaces because you questioned the official narrative on lockdowns, vaccine mandates, the Ukraine war, January 6th, or whatever, you will likely encounter oddball propaganda like this tailored to your likes and dislikes.

As outlined in “Countering cognitive warfare: awareness and resilience” by NATO Review, there is a clear understanding that the increasing deterioration of the human mind produces fertile ground for successful cognitive warfare campaigns.

Our weakened state of mind is what makes cognitive warfare so effective:

Our cognitive abilities may also be weakened by social media and smart devices. Social media use can enhance the cognitive biases and innate decision errors. The rapid pace of messaging and news releases, and the perceived need to quickly react to them, encourages “thinking fast” (reflexively and emotionally) as opposed to “thinking slow” (rationally and judiciously).

Yes, our weakened minds have been and continue to be thoroughly studied. Our impulses, passivity, emotional usurpation, etc. are well documented, well known, and are now being harnessed against us.

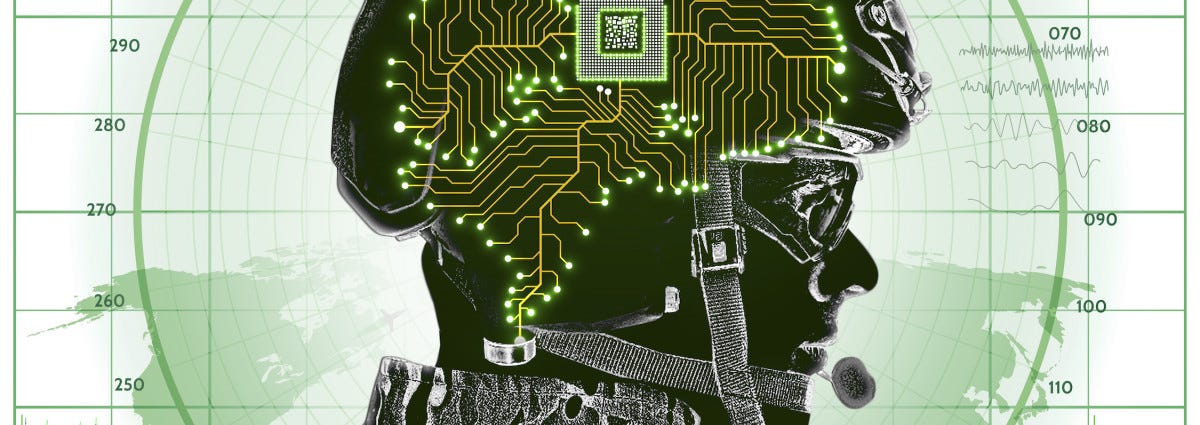

The militarizing of the collective cognitive sphere is not possible without the development of some extremely powerful tools and entities such as our devices, big tech, social media platforms, the mainstream media, teams of social scientists, and possibly most notably, artificial intelligence mechanisms that collect, store, organize, collate, and produce directives based on an unfathomable amount of data. These entities and tools are both the cause of the deteriorated state of mind as well as the vehicles through which we can be attacked as a result of this state of mind.

The Minotaur

The story that inspired the images in my newsletter . . . a picture of the mind made clear.

This is the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, or the story of Ariadne’s golden thread.

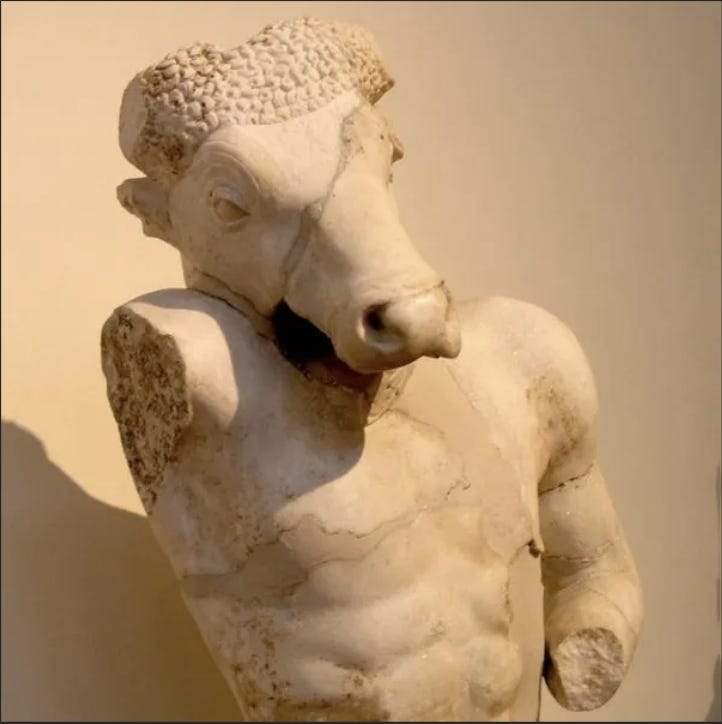

The famous Greek myth tells the story of Theseus, son of Aegeas, the king of Athens, and how he conquered the Minotaur. At that time, Athens was under the control of Minos, the King of Crete, who had a great underground labyrinth built beneath his palace on the island of Crete. In the center of the labyrinth, he put a terrible monstrous creature, half-man half-bull, called the Minotaur.

The Minotaur fed on human flesh. To satiate it and keep it alive, King Minos demanded that as a form of taxation on Athens, Aegeas must send 14 Athenian youths — seven maidens and seven young men — to be devoured by the Minotaur every nine months. No one ever found their way back out of the labyrinth. Theseus, against his father’s wishes, insisted to go as one of the sacrificed youths in order that he might kill the Minotaur.

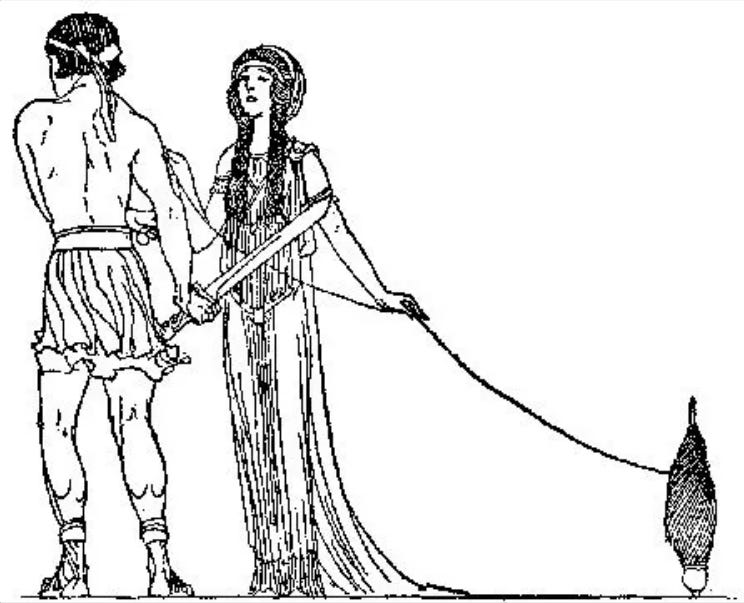

While the 14 youths were paraded through the streets of Crete on their way to the underground labyrinth, Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos fell in love with Theseus and determined to help him. She gave him a ball of golden thread and instructed him on how to find the Minotaur once within, and how to find his way back out of the dark labyrinth. Ariadne had gone to the priest who had designed the magical labyrinth to learn its secrets which she passed along to Theseus.

She helped Theseus attach the golden string to the entrance of the labyrinth and instructed him to slowly unravel the ball as he wound his way to the center. Theseus was then able to find and slay the Minotaur. Following the slaying of the Minotaur, Theseus was able to follow the golden thread, bringing the other 13 Athenian youth back out of the labyrinthine darkness into the light of day.

The labyrinth has always been a pictorial representation of the mind. What the Minotaur stands for has been a subject of interest and debate for a long time. Suffice it to say, the Minotaur represents something that has taken residence within the mind connected to control, servitude, and death. Theseus the hero, though strong and brave, needs the wisdom of Ariadne and the willingness of the labyrinth’s creator to find his way back out to the light of day, even after the labyrinthine mind had been purged of the monster.

These two images associated with Beyond the Maze represent Cretan labyrinths. One, an ancient Greek coin, the other a rendition by artist Mark Wallinger from his “Labyrinth” series.

NATO’s imagination of the labyrinthine mind:

What is your Minotaur. What is your golden thread?

The Mad Farmer

The poem that inspired my newsletter’s raison d’être.

Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front was written by Wendell Berry in 1973. Though 50 years old, I find its shockingly relevant today.

The poem begins:

Love the quick profit, the annual raise,

vacation with pay. Want more

of everything ready-made. Be afraid

to know your neighbors and to die.

And you will have a window in your head.

Not even your future will be a mystery

any more. Your mind will be punched in a card

and shut away in a little drawer.

When they want you to buy something

they will call you. When they want you

to die for profit they will let you know.

The poem’s first few lines describe the modern American, distracted by illusory life goals such as wealth and convenience, going on to develop a completely predicable and therefore easily manipulated state of mind.

The artificial intelligence mechanisms can collect, store, organize, collate, and produce directives based on an unfathomable amount of data. How many of the cognitive warfare campaigns unleashed on citizens involve directives produced by machines?

Cognitive warfare is predicated on the idea that AI, or machines, could know everything there is to know about us — or at least enough to recreate a comprehensive digital avatar of each of us that perfectly reflects our individuality. Cambridge Analytica bragged in 2016 that they had collected 4,000-5,000 data points on over 220 million American citizens.

Terms such as “psychographic segmentation” and “individually specific confirmation bias micro-targeting” reflect an effort to compile enough data specifics to target each person individually. But can everything, or enough, ever truly be known? Where “not even your future will be a mystery”?

The Wise Child

My recent conversation with an eight-year-old.

Him: Wouldn’t it be cool if you made a video of your whole life and then someone else could watch your whole life like a movie?

Me: Well, it would take someone’s whole life to watch someone else’s whole life on video. Wouldn’t you want to do other things with your life and time as well?

Him: I just think it would be cool to try to know everything that happened before and after your life.

Me: Do you really want to know everything there is to know?

Him (after long pause): No

Me: Why not?

Him: Because then you’d have nothing to learn, and I like learning things.

Whatever compels the second grader to trade in unlimited knowledge for the love of learning is a secret that, in my opinion, will always remain out of reach to the AI no matter the level of sophistication achieved.

It is a tricky-trick of the mind through the abuse of language to say these machines can learn, or make decisions, comprehend, are intelligent, or any other such bunk. The AI computes. That’s it. If we can thoroughly define the difference in our own thinking between learning and computing, we may be led to ask the question, What can’t the AI compute? I think this question is a good lead to finding our way out of these coercive trappings; a golden thread if you will.

Perhaps we are predictably stuck in a never-ending intellectual debate. Predictably clicking resend. Predictably thinking online information will “wake people up.” Predictably forever trying to figure out how to better argue our points. Predictably ready to consume anything that comes our way with which we agree (click resend).

Perhaps there’s something to becoming less predictable, more like the fox?

Berry’s poem continues:

So, friends, every day do something

that won’t compute. Love the Lord.

Love the world. Work for nothing.

Take all that you have and be poor.

Love someone who does not deserve it.

Denounce the government and embrace

the flag. Hope to live in that free

republic for which it stands.

Give your approval to all you cannot

understand. . .

As soon as the generals and the politicos

can predict the motions of your mind,

lose it. Leave it as a sign

to mark the false trail, the way

you didn’t go. Be like the fox

who makes more tracks than necessary,

some in the wrong direction.

Practice resurrection.

People do not like to admit when they have been had. If we were honest with ourselves and looked at our dealings with our devices and the media content we engage with through them, we would admit that we are swiftly losing agency over our minds.

The intricacies of this phenomena are being mapped almost exclusively by those who would take advantage of us, not help us. Let us flush out our Theseus heroes, our Ariadne wise women, our magical priests. It’s time we start mapping this labyrinthine landscape ourselves!

This is the archetypal hero’s journey. identifying our inner Minotaur is serious business.

What if the war we are fighting is ultimately within ourselves?

On one level it is an outrageous and offensive question.

On another level it is a challenge to look ever more deeply within to possibly behold what we most do not want to be true; what we most emphatically are NOT. (THEY ARE!)

My contempt, tyranny, lies, and cruelty. Sitting with them as best I can right now, not perfectly but always aiming higher, with compassion, choosing to bear the ultimate responsibility of healing myself, because I see the world as much as I am as I see it as It Is.

What if we continue the hard labor of forging peace and justice in the world, while each of us shoulder the compassionate labor of peace and justice: Integrity, within?

The practice of the question nourishes the seed of becoming the change I/we wish to be in the world.

Wow, loved the poem!